BY MATTHEW ENG |

How GOODFELLAS Became Scorsese's Most Misunderstood Masterpiece

It's not Scorsese, it's you.

Written on the occasion of Goodfellas' 25th anniversary.

In 2013, New Yorker television critic Emily Nussbaum posited a provocative but necessary theory on the joyless rise of the "bad fan," i.e. the die-hard viewers who have turned prestige-laden protagonists like Tony Soprano, Walter White, and Don Draper, among other middle-aged, middle-class, and — importantly — white male leads, into cultural idols. If these "bad fans" had their way, Breaking Bad would be comprised entirely of Bryan Cranston taking names and threatening competitors in huskily menacing whisper, The Sopranos would be nothing more than grisly offings and Bada Bing! scenes, and Mad Men would be reduced to an endless loop of Don Draper bedding nameless sixties bimbos in a cumulus cloud of Lucky Strike smoke. (And, needless to say, Skyler, Carmela, and Betty — that astonishing but oft-denigrated triptych of “Difficult” Wives — would be nowhere in sight.) This bluntly "badass" form of idolatry has threatened to scrub out the warts-and-all subtleties of these prodigious shows, diminishing these landmark one-hour classics to empty, reflex exercises in machismo.

Even though the "bad fan" phenomenon has gained traction as a TV mainstay in recent years with the rise of the cable drama antihero, its seeds have been deeply sown and its roots stretch as far back as James Cagney, that original toughie, smacking a grapefruit square into Mae Clarke's face in 1931’s touchstone gangster drama Public Enemy. That notorious scene — played straight but frequently misinterpreted as comedy — can be found on YouTube, with a hotbed of top comments that each grossly summarize typical "bad fan" reactions: "That was supremely funny," "Ah the good ol days hahaha," and, most chillingly, "She'll stay with him. And that's why men rule the world.” At what point does inappropriate appreciation become stomach-turning misogyny?

Of all genres, it is the gangster drama that most often attracts hero-worship of this troublingly hardline variety. Moviegoers have revered the gangster archetype since the dawn of Hollywood: these were the days when a pug-faced character actor like Edward G. Robinson could be a legitimate leading man so long as the role was a snarling heavy and Bogart was still playing the B-movie hood, an unsavory image he never entirely shed and which was indelibly emulated and further solidified by Jean-Paul Belmondo in Breathless. Viewers, mainly but not solely male, cling to these types as movie-certified masculine ideals, building a bridge that connects Bogie, Cagney, and Robinson to Scarface, The Untouchables, and the lad-land crime comedies of Guy Ritchie’s early oeuvre, not to mention the holy troika of Coppola's Godfathers.

But of all these films—many great, other less so—it’s Goodfellas, Martin Scorsese’s majestic mob masterpiece about real-life hood turned Witness Protected informant Henry Hill, that has gained the most unsettlingly off-base appreciation from some of its most avid loyalists, the type who know every named mobster’s nickname and can recite them in the order they’re introduced.

Goodfellas is one of my favorite films, a stylish, daring, and endlessly engaging tour de force that maybe isn’t Scorsese’s finest masterpiece — and with a résumé like that, who’s complaining? — but which nonetheless draws me in and reveals a little more of its nasty, hypnotizing self with each and every new viewing. But Goodfellas is also the Scorsese masterpiece whose enduring pop cultural legacy leaves me the most frustrated, as many of its (loudest) fans continue to regard it as something like a pure comic diversion, which it occasionally is, but often connotatively so, as in that brilliantly sick non-sequential opening sequence, which acquires deeper, darker, and sharper significance once we catch up to it within the chronological frame of the film. Even worse than the straight-out comedy label, though, is the irksome tendency to view Goodfellas as nothing more than an “ultimate male fantasy.”

At least that’s the attitude that was assumed by New York Post film critic Kyle Smith, who back in June penned an infuriating piece entitled — and, honestly, I feel my eye twitch just thinking about this title — “Women are not capable of understanding ‘Goodfellas.’” Excusing the fact that the film was actually cut and shaped by a woman (that would be Scorsese’s longtime collaborator and editing legend Thelma Schoonmaker), Smith’s article basically suggests that what Sex and the City was for women (i.e. escapist, wish-fulfillment art, which it wasn't), Goodfellas represents for men, a dunderheaded argument so hoarily out-dated that I’m pretty sure it would make a caveman groan. It’s not a novel opinion and — to an extent — I understand it. What could be more desirous to the standard male viewer than a glitzy-gritty vision of virile power involving guns, gals, and an endless cascade of cash, unencumbered by care or consequence?

That’s an entertaining movie, but it’s also not Goodfellas, which fans like Smith seem intent on branding, with misplaced nostalgia, as some sort of “OG male buddy flick,” as though Goodfellas were a precursor to The Hangover or Scorsese had made Diner, but with whackings and wiseguys. Smith enthuses that, to guys, Goodfellas’ central trio of conspirators — Ray Liotta’s Henry, Robert De Niro’s Jimmy Conway, and Joe Pesci’s Tommy DeVito — are “heroes” and “[rulers] of the roost,” buying into the myth of lawless heroism that these men ascribe to themselves rather than what is being suggested with more subtlety by the filmmakers. This is Bad Fan Behavior 101. When it comes to reactions like Smith’s, one must always inevitably wonder if the director (or showrunner) is to blame for these dubious takeaways, as Breaking Bad mastermind Vince Gilligan recently had to answer for when actress Anna Gunn become the target of death threats over her intensely divisive performance as Skyler White, or when Boston Bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev claimed that the show had taught him to, among other things, successfully dispose of a body.

In instances like these, it’s hard to blame an artist like Gilligan, whose show never fully fed into the outlaw adulation that its fans so passionately projected on to Walter White and who can hardly be accused of creating a violent provocation, much less a criminal instruction guide. Scorsese, too, doesn’t warrant the blame for the chauvinistic vein in which Goodfellas’ bad fans have appropriated the film’s legacy to fit the superficially cool story they’d like it to be. (And between Taxi Driver and The Last Temptation of Christ, Scorsese has infamously seen his share of director-shaming misinterpretations.) Scorsese is, quite simply, far too talented and too intelligent a filmmaker to have made the movie Goodfellas is labeled as. In his eyes and in the eyes of those searching for more than just compulsive entertainment, which Scorsese provides in spades, Goodfellas is — in its most basic form — a gutsy and rigorous immersion into the life of a desperate, cantankerous man who continually goes to great and often dangerous means to achieve his all-consuming desire of money, power, and glory, which is a narrative that could be applied to any number of American movies, from Citizen Kane to Birdman.

There has always been a certain level of ornamental excess to Goodfellas and Scorsese’s filmmaking in general (that tracking shot! that soundtrack!) that often threatens to gloss over the ethical decrepitude that dwells at the film’s core with pop-colored, bullet-riddled grandeur. But Goodfellas isn’t a party. As Roger Ebert, who "got" Goodfellas and Scorsese better than almost any critic and famously trumpeted the film over The Godfather as a different but more accomplished depiction of organized crime, noted in his original review, “[The] camaraderie is so strong… But the laughter is strained and forced at times, and sometimes it’s an effort to enjoy the party…”

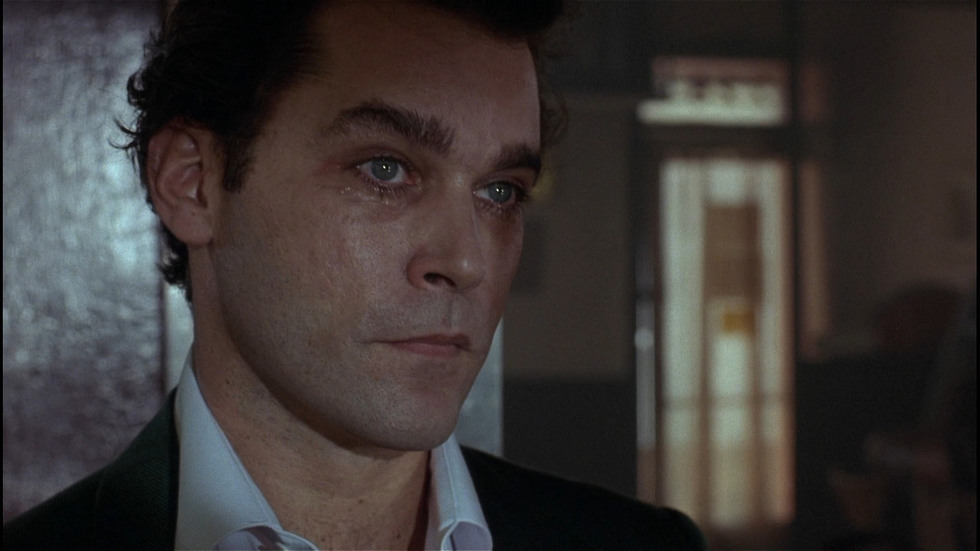

Even as Goodfellas coats a glittering sheen over most of Michael Ballhaus' marvelously multilayered images, Scorsese delves pretty deeply into the foolishly warped mind of Henry Hill, whom he pegs almost instantly as a craven, class-A manipulator. Liotta, who is truly the unsung hero of Goodfellas' success, is Scorsese’s invaluable accomplice in this regard. There is far too much bugginess in Henry’s eyes and too much flop sweat that accumulates on Liotta’s forehead throughout the film to make Henry a hero, not to mention the fact that he’s an abusive and unfaithful husband to his persistent wife, Karen (Lorraine Bracco), who isn’t merely the emasculating “ball-buster” that Smith pins her as, but rather a spunky, idealistic woman who unravels under her husband’s carelessness before realizing that blithe ignorance and casual culpability are her only possible options. Meanwhile, Henry’s relentless pursuit of criminal aims allows him to become the type of made man he deified as a boy, a transformation that is firmly rooted in the heroic images of his departed youth, when he was initially recruited into mob society. In many ways, Henry is the prototypical Goodfellas bad fan.

From there, Scorsese and co-writer Nicholas Pileggi are ultimately less interested in creating heroes than in deconstructing Henry and his friends. Tommy, the volatile live-wire immortalized by an Oscar-winning Pesci, has become Goodfellas’ iconic character, for better and for worse. Pesci’s classic “Funny how?” interrogation can be recited with stunning alacrity by any number of fans, who quote it like a comic routine when it’s a really a self-conscious tantrum.

Pesci’s character is always cited as “unpredictable,” but Scorsese and Pileggi patently delineate Tommy’s violent outbursts (the aforementioned monologue, the murders of Billy Batts and “Spider”) as excessive defense mechanisms against potentially humiliating forces that seek to call his authority into question. “Jimmy the Gent” is one of De Niro’s most understated characters, whom we too often misremember as a coolly elegant portrait of gangsterdom, even though Jimmy’s clearly enough of a frantic creep to gutlessly set up Karen near the film’s finish. And Liotta gets saddled with what has to be one of the most pathetic sights in cinema history, as Henry and Karen shrilly sob on their bedroom floor after the latter throws out some leftover cocaine that was their only source of profit. It’s an extended scene that Scorsese makes purposely uncomfortable, forcing an audience tempted to root for Henry to see what such “heroism” looks like in the harsh light of reality.

Scorsese possesses and expresses razor-sharp ideas about his characters and their riskily illicit circumstances, their despicable behavior, and their frequently self-imposed stresses, but he has never been a filmmaker particularly interested in passing decisive judgment on his characters, or, more specifically, gravely moralizing their actions so as to make his story totally edifying or disciplinary, which perhaps explains why so many viewers have frequently latched onto Goodfellas’ surface appearance, ignoring the ironic value beneath it all. In an essay appreciation of Pietro Germi’s Divorce, Italian Style, in which Marcello Mastroianni’s Sicilian sad sack attempts to off his suffocating wife, Scorsese described Germi's pitch-black comedy of errors, manners, and re-marriage as “a very moral film, but there’s nothing superior about it because it’s criticizing a whole culture rather than an individual,” a particularly trenchant task that Scorsese’s film also boldly tackles.

Underneath the polished photography and jukebox palette of Goodfellas, lies a penetrating critique of the extremes of estrangement, chauvinism, cruelty, criminality, erotomania, and regression that certain communities, cultures, and countries will allow their men as they ceaselessly chase after their own selfish desires. It’s a brutally urgent analysis that I suspect will continue to be ignored by the film’s biggest and most oblivious admirers. Then again, maybe they aren't oblivious at all to the movie's permeating message. Maybe they’re just unnerved by how true it still rings.